Ever wonder what climbing New Hampshire’s notorious Mt Washington is like in the winter months? Well, this article will give you one climber’s perspective: a personal account given by someone with sixty ascents, over half in winter. Enjoy. –Mike Cherim, NEM Guide

The training is done, the gear packed, and the stoke is on… all is ready. Sure, the forecast could be better, as often is the case on the deceptive 6288′ Mt Washington — the highest point in the Northeast and notorious for its extreme weather — but the winds should remain less than hurricane force and the ambient temperatures might actually top out above zero. It’s a go.

The wind howls through the icy parking lot at the AMC’s Pinkham Notch Visitor Center. I look up and see a massive shroud over the bulk of the mountain before me. I shudder and shiver and make my way to the building where I sign in… and hopefully sign out many hours later. I perform a last minute check of my gear then head outside again.

I start up the Tuckerman Ravine Trail feeling a bit chilly. I know if I start my ascent feeling toasty and comfortable, I’ll be overheating very quickly and risk sweating. I don’t want to sweat. “To sweat is to die,” they say. I want to live; I want to stay dry. I still get warm and by the time I reach the Crystal Cascade I’m comfortable in just my heavy base layer top. I can see my breath and my nostrils freeze shut a bit when I inhale, but the exercise makes me warm. I feel great.

Mt Washington is not easy. I realize this soon after the start of this wide but continuously rising trail. I will have to earn this one, I can tell. I struggle with my thoughts as I focus on the pain, but eventually I fall into a slow but steady rhythm and forget. I concentrate on putting one foot in front of the other. Every once in a while I notice a stand of conifers or other pretty sight and I smile. It’s beautiful up here.

I climb steadily for about an hour when I realize I must stop. I had a good breakfast but I am hungry. After putting on a heavily insulated jacket so I don’t get cold, I eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, drink a good amount of water, and sit on my pack while keeping my gloves warm and dry in my jacket. The rest feels good. I don’t dawdle, though; I don’t want to allow my muscles to cool too much.

I climb steadily until I reach the Fire Road and I take a right toward the winter route of the Lion Head Trail (the summer route is an avalanche danger zone and is closed). I reach a litter-containing first aid cache — a reminder of the seriousness of this mountain — and stop again, but only long enough to put away my trekking poles, take out my ice ax, and put on my crampons. I work quickly, again so as to not allow myself to cool down too much.

Soon I’m climbing again. At first it’s not steep, but it doesn’t take long to see the pitch increasing. My quads and calves are very warm. I press on and a bit later I come to a semi-technical choke-point humorously referred to as the Hillary Step (named after a feature on the south side of Mt Everest). A group prompts me to pass them so I take the offer and continue on. Some will use a rope here, but today I’m not since the footing is good.

I am very focused here. Very focused on the muscle pain, very focused on my heart, and very focused on the route as I need to be. A slip and fall here could be bad. Not deadly, probably, but almost certainly painful. I maintain a slow and careful cadence, with a rest-step pause on each leg resting on my skeleton. I plant my ice ax, kick in my crampons, then push hard with my leg pushing myself ever closer to the summit. It’s too early to speak of summits just yet, however.

I pass the steepest sections, but the vertical push on this eastern ridge is significant and continues steeply for a good distance. Eventually the trees around me are very small and before me lies a barren snowy, icy, and rocky alien-looking landscape. I see intricately wind-scoured sastrugi snow, near-buried krummholz, and rime feathers adorning everything facing northwest. It’s foreign and amazing. I put my jacket back on and have another handy if I need it. I also put on a balaclava and glacier glasses (my preference over goggles), as well as eat and hydrate once again.

I leave the relative safety of treeline and climb into the expanse. Not to sound crass, but I head into the shit, so to speak. The wind whips and blows snow into the air. The clouds swirl around me, sometimes obscuring my vision as fog. I see the carefully built stone cairns, though, so I am able to keep my direction. It’s not as steep as it was, but for the next half mile it is still arduous. I press on. Every once in a while I snatch a peek of the Boott Spur summit on the opposite ridge to the south.

I reach the pronounced rocky outcropping known as Lion Head, but before clearing the top I stop again to rest, eat, drink, and re-assess. I do this always. I don’t wish to succumb to summit fever so I make safety considerations before deciding to continue. Once I clear Lion Head the wind will be fiercer than ever, and while Mt Washington isn’t the biggest mountain in the world, it packs one hell of a punch.

The wind is blowing around forty with gusts hitting the sixties. It’s a west-northwest wind but the flow is curving around the ravine and coming in from the west-southwest and hitting my left side. It’s tough walking. It flattens out after Lion Head but the rocks are wind-scoured offering little snow to walk on; it’s mostly rock and ice so the footing is a challenge and with these winds, bordering on dangerous. These risks are part of it. If it was easy everyone would be up here. It’s not; they’re not. But the winds will subside as I reach the shadow of the summit cone. I’ll have relative peace once again.

I press on and soon pass the Alpine Garden Trail junction on my right and enter some low scrub. In the summer this low scrub easily clears my head obstructing my views. But now I stand proud; the snow is very deep. As I continue I reach a large bisected snowfield, where the snow is 20-feet deep or more in spots. This part is just over three-tenths of a mile but some dislike it. A trudge. It goes fast, I think. No cairns. Just a boot track, or a compass bearing if need be. One foot after another. Sometimes I place some bamboo wands so as to mark the path back. It’s important since the summit is only half-way.

The views, when the clouds thin, are amazing — and alien. The end of the snowfield’s climb brings me to “Split Rock” where I once again fuel up and reassess. All systems are go. I make my way through the split and enter the maelstrom once again, no longer protected by the cone as much as I was. Now comes the push. Three-tenths to the Auto Road; one-tenth to the summit sign from there.

I am cocooned in protective layers: specialized base layers, a soft shell, a hard shell. The inside world, the outside world. I keep them separate. I hear my breathing and feel my heart on the inside. Outside the wind. The ascent of the cone isn’t super steep, but it is steady, and like most of this mountain, it’s demanding. Borderline relentless — though not really, not for someone in reasonable shape. I focus on my breathing. I can hear it. It surrounds me in my inside world while the wind whips my outside world into a frenzy. I also focus on my footing. I do not forget to look around because what’s reaching out from me in all directions is hell in gray and white. A wasteland of rock, ice, snow, dormant alpine grasses and tiny plants in places, lichens, and nothing else. The wind prevents anything from growing here. I cannot survive here but for only a limited time. But it’s freaking beautiful!

I climb upward. One step at a time. I am not sore, but I feel my strength waning a bit. My pace slows to a true rest step. I am tiring. The goal is near, though. I know it. I sense it. I press on. Before long I spot something, a red cylinder or something, but quickly the clouds consume it. A few minutes later I spot a sign post. I have reached the Mt Washington Auto Road. I don’t worry about cars — or the Cog Railroad — but I do keep an eye open for the State Park’s or Mt Washington Observatory’s Snow Cats.

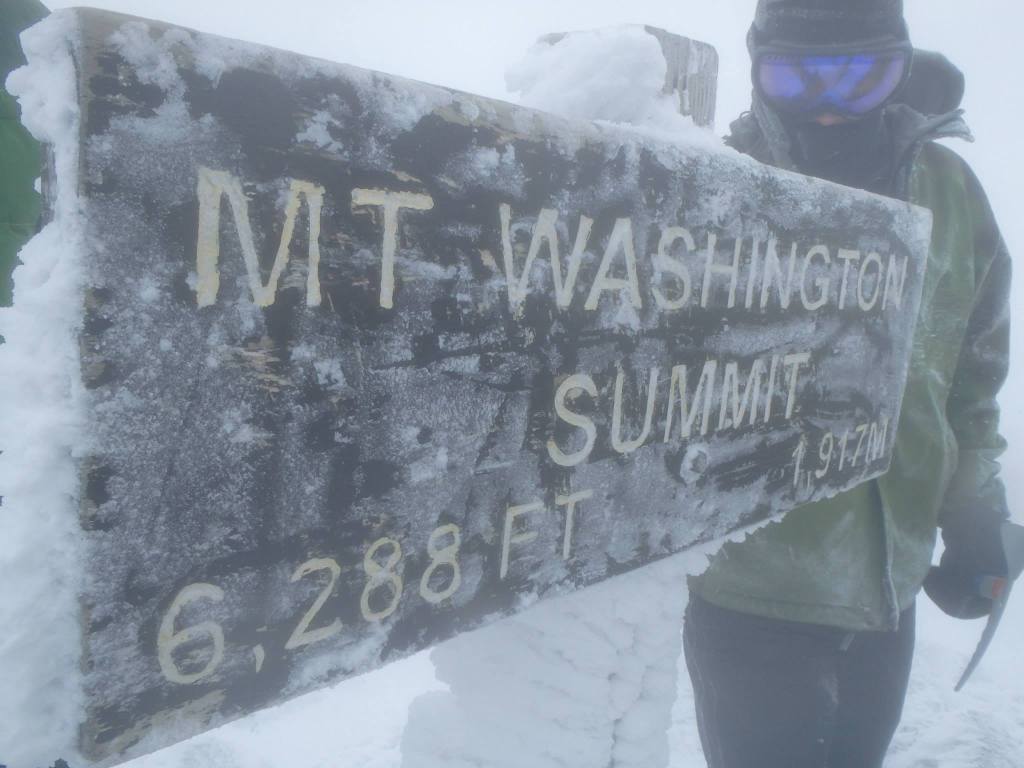

I now walk on icy asphalt and snow. I can tell it’s a road. It’s hard to see up here at times, but I know where to go and head to the stairs. I can’t take them; they’re closed off. Apparently they don’t want climbers chewing them up with their crampons. I climb alongside the wooden structure and quickly hit the summit plateau. The heavy lifting is done, as they say. I walk toward a pile of rock situated near the center of a frozen campus of buildings, including one structure of rock called the Tip-Top House. Very cool. Atop this pile of rock is a summit sign. I make my way to it for a quick photo. I made it to the half-way point. I then down-climb and seek shelter among the buildings. (Note: This year, due to summit construction, the old “Cat garage shelter” may be inaccessible so climbers may have to rely on the leeward sides of buildings or get under the end of the Cog tracks, as I’ve been told. At the time of this writing, it’s not exactly clear what’s available.)

I am getting cold. It’s not a living-creature-friendly place so after a short stay including a snack and some water I begin my descent. I partially plunge-step alongside my old boot track, and I partially make my way over rocks. Since there is little cardio effort involved, it goes much more quickly. To the skilled and sure-footed this phase can be more a less a controlled fall. Speaking of which, some ski down the mountain.

I’m enjoying myself. The wind is from my right now, and slightly behind making itself less known. I quickly gain “Split Rock,” then the snowfields, then the Alpine Garden and Lion Head soon after. I’m warm, but it’s the descent so I’m not sweating too much considering how quickly I can move. I’m elated. I’m not done, though, not by any means. My focus must remain razor sharp. The descent is filled with perils. I could hook a crampon, sink a foot into a hole, any number of things.

I continue downward and soon make the safety of treeline. The most dangerous parts of the mountain behind me. That said, I still have the steep sections to go and I have to down-climb them which is more difficult and more dangerous. I’m careful, though, and with the help of my ice ax and careful foot work, knowing through experience what I can and can’t get away with, I make it down safely and expeditiously.

I reach the fire road and decide conditions will allow me to remove my crampons so I do. I also stow my ice ax and take my trekking poles back out. I still have plenty of daylight since I made good time so I leave my primary headlamp in my pack. It’s really a blur from here. I swiftly move down the Fire Road and onto the Tuckerman Ravine Trail. Gravity does the rest, I just stay on my feet, along for the ride. Before I know it, passing familiar sights along the way, I reach the start of the trail. I remember to sign out then head towards town. It’s time to celebrate. Only now can I say it’s done.

We are proud to work with the Department of Agriculture, the White Mountain National Forest and the Androscoggin Ranger District where we are authorized outfitter guides.

We are proud to work with the Department of Agriculture, the White Mountain National Forest and the Androscoggin Ranger District where we are authorized outfitter guides.